Artful Grief

Author: Sharon Strouse

A Journey of Healing

When I conduct workshops and stand in front of grieving military families at TAPS seminars, I stand not only as an Art Therapist, but as a mother who has suffered loss. On October 11, 2001, I received a phone call from the New York City Police Department telling me that my seventeen-year-old daughter Kristin had fallen from the roof of her college dormitory. Kristin had succumbed to a mental illness and taken her own life. So began my journey into the labyrinth of grief, one that I continue to walk, one that is ever evolving and changing with time.

We are bound by our stories of loss, bound by heartache, and bound by our healing journeys. One of the greatest gifts the bereaved can give is to share what worked and how it worked. I found healing in the creative process of my art, making collages, one after another. I cut and tore images out of magazines and pasted them on various sizes of colored foam board. I visited and revisited the territory of Kristin's death. Over time there was transformation and healing. This worked for me and this is what I now share with others. This is a story of how art heals.

In the months following Kristin's death, concepts were not helpful to me. I did not take comfort in knowing that death was universal and a part of our shared experience as human beings. I did not take comfort in knowing that grief and bereavement were normal, highly individualized human processes. I was in pain. My body and soul ached.

I found comfort in traditional therapy as well as two peer support groups—The Compassionate Friends and Survivors of Suicide. I found additional comfort in the creative process of collage which I embraced a year into my bereavement. I found that it quieted my mind and opened my heart to healing in ways not previously experienced.

For many who grieve, the intensity of the emotions eases naturally, but for a small percentage, the feelings of loss are long lasting and incapacitating. This is known as complicated grief. My grief was complicated.

For those who grieve a military death, there are also factors that may “predispose survivors to complicated grief,” according to Dr. Jill Harrington- LaMorie, a military survivor herself who now works on the National Military Family Bereavement Study at the Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress. The exposure to both grief and trauma leaves some survivors at risk for developing complicated grief and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.

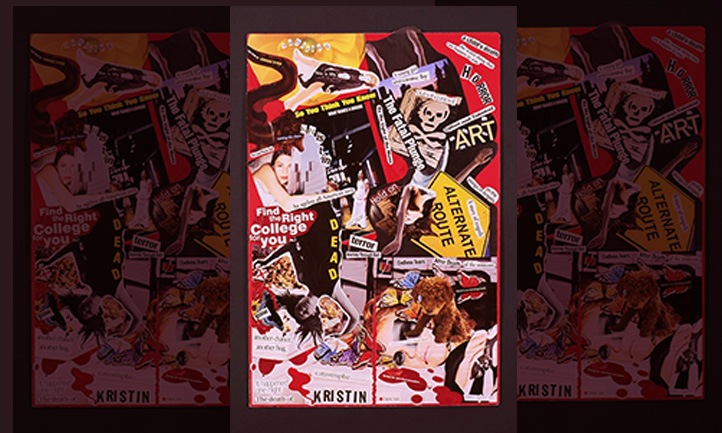

One element of my complicated grief was a visiting and revisiting of the moment Kristin died. This “event story” was difficult to talk about because of its violence, but the unspeakable found a way to be seen and heard through the collages I created. There was release, for the telling and retelling was an important healing element.

“These acts of making and sensing, or ‘sense making,’ are ways of knowing, shaping, and storying grief and loss,” say Doctors Thompson and Berger in their writings on expressive arts therapy and grief. “This way, experiences do not remain ‘sense-less,’ silenced, unseen, immovable, or untouchable.”

In January 2002, after completing my first three collages, I created collage number four, titled “Suffering.” The 20 x 30 inch red foam board held the fragments of my story. When I sat down to begin, I did not plan to touch the violence; it happened as I came across the image of a young girl with butterflies in her hair. I looked at it and saw Kristin on the concrete. I imagined red everywhere. I could easily have turned the page; instead I tore it out and glued it down. I looked at it.

In my journal I wrote, “I glue you down in a way that allows the rupture to be seen. I like the torn edges and leave them. There is some kind of physical release in the experience of tearing. I tear and align myself with the truth of the exposed ragged and uncontrolled edges of your death. Cutting with scissors produces a different experience; there is more control. It is clean and neat. There is nothing clean or neat about death… I place another image of your descent into my space. My attention rests in the wound of your death.”

I spent hours each day for weeks working on this collage. While a candle burned, I played soft music and found a way to let go. I let go by allowing those images to come into form. Their strength and power diminished over time. The energy of creating provided a safe and still place for the trauma to rest. The revisiting felt compassionate. I found a measure of calm and peace through the process which infiltrated the rest of my life. My nervous system quieted.

Over the years I revisited the “event story” whenever it came to mind. It was part of the beauty of art, one of the healing properties that allowed what was unconscious to become conscious. I moved, not in circles, but in an upward spiral, coming to that moment from a different place in time and a different place in my healing journey. According to Thompson and Berger, “In expressive arts therapy, an attitude of openness and receptivity invites images to appear and allows them to find their appropriate forms.”

After four years and 17 more collages, I created collage number 22, titled “Silver Death.” Five years after Kristen’s death, the “event story” image was simple; there were no parts and pieces. There was integration. What was broken and shattered had become whole.

In my journal I wrote, “She almost shimmers. She is in a prayer-like position, eyes downcast, and arms hidden within the folds of her dress. She is pure energy. She holds all of you, both your life and death. Death reaches her hand out beyond the mirror’s frame and drops a red rose into the field. Flesh appears on the hand of the skeleton. Life does come back slowly, bit by bit. There you are with your bunny rabbit and angel wings. You have a wreath on your head, reminding me of the gold beaded headband we buried you in. You were sweet and innocent then and I am able to experience your sweet innocence still, even with your suicide. You are held in silver grace, your blood a rose."

After so many years of dealing with the torments of Kristin's shattered body, it was a relief to see her angelic. In that moment, the image of her death appeared spiritual and peaceful.

Making art heals. These are the words I weave throughout the workshops I offer during my times with TAPS. I watch as the bereaved come into our Rita Project Open Studio. I watch as survivors find courage and allow their stories to move through them and onto the blank pieces of paper. I watch as they shed tears and soften. I am not surprised, but they are often surprised at how much better they feel after being in and with the stories they keep inside.

Paper, scissors, and glue are all you need. No talent is required, only the willingness to explore your grief, artfully.

By Sharon Strouse, MA, ATR: Sharon Strouse holds a bachelor’s degree in Psychology and a master’s degree in Art Therapy. Her collage making process, in response to the trauma of her daughter’s death, developed into a template for work with others. She is a sought-after workshop presenter, author, and artist. Her private practice in Baltimore, Maryland includes art and meditation (www.attherefuge.com). Sharon is a director for Rita Project: Baltimore, devoted to using the arts to help those who have lost someone to suicide and those who have attempted suicide to connect with the power of creating (www.ritaproject.org).

By Sharon Strouse, MA, ATR: Sharon Strouse holds a bachelor’s degree in Psychology and a master’s degree in Art Therapy. Her collage making process, in response to the trauma of her daughter’s death, developed into a template for work with others. She is a sought-after workshop presenter, author, and artist. Her private practice in Baltimore, Maryland includes art and meditation (www.attherefuge.com). Sharon is a director for Rita Project: Baltimore, devoted to using the arts to help those who have lost someone to suicide and those who have attempted suicide to connect with the power of creating (www.ritaproject.org).